PAUL MCBETH: Eighteen years of KiwiSaver and we still spend more than we save

It’s about time we stop living in the moment.

Paul McBeth is the editor of The Bottom Line and Curious News, having worked at BusinessDesk for 15 years. His KiwiSaver has been with Milford Asset Management since 2014 and he rents from a private landlord in the Auckland CBD.

If KiwiSaver was a person, it’s now old enough to buy a six-pack and a vape, die for its country and vote in next year’s election, but it still hasn’t cooled our inclination to spend our paycheque and then some.

In fact, since its introduction in July 2007, households’ net savings have increased just $786 million.

In the 38 years spanning 1987 to 2024, we’ve been net savers in just 16 of them and half of those were before things really turned south in the mid-1990s.

That might seem counterintuitive.

KiwiSaver funds have grown to $130 billion or so in 18 years, and managed funds more generally oversee assets totalling $341 billion, compared to just $73.95 billion before the government-sponsored savings scheme launched. Not to mention the increase in deposits – largely at banks – to $268.16 billion from $82.84 billion.

But in terms of what’s left over from household disposable income after general expenses and capital purchases (ie housing), we tend to eat our nest eggs as soon as they’re laid.

No saving grace

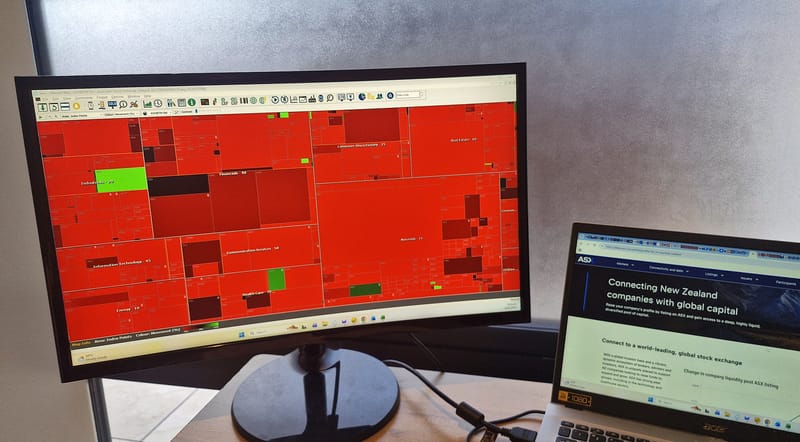

In the March 2024 year, the household net savings rate was minus 1.6%, or minus $3.68 billion, deteriorating from minus 3%, or minus $6.75 billion, the year earlier, which had been the worst year for dis-saving since the March 2007, just before KiwiSaver was launched.

And to be fair, drawing on your savings during the never-ending recession is exactly what it’s there for, especially after a super-charged savings year in the March 2021 period, when households’ net savings rate of 7.6% feathering the nest to the tune of $15.1 billion.

The thing is, we love to spend – and not just on property.

Retail sales volumes – adjusting for inflation – have climbed 52% since the March 2007 year, outpacing population growth of 26%. And at a raw value level, we’re spending twice as much on core retail goods, while salaries have gone up a more modest 53%

This isn’t a new problem, and we need activity to keep the economy from sliding into a doom spiral, even if we rely on overseas money to pay for it.

Go back to the 1990s and 2000s and you can find all manner of reports trying to fix New Zealanders’ propensity to leave saving to the government, and put their own money into the family home.

Always bet on the houses

Little wonder that the total value of New Zealand’s housing stock was $1,642.55 billion at the end of March, up from $605.01 billion in June 2007 before KiwiSaver arrived.

It might not have grown at the pace of managed funds, but in aggregate terms that’s a trillion dollars. If you think about it in terms of our productive economy, gross domestic product is only $430 billion and a mere $172 billion back in 2007.

That doesn’t come cheap either. For every dollar of our net disposable income, we’re borrowing $1.63 to finance a mortgage – back in 2007 that was $1.56.

If you want a big hairy number, we’ve collectively borrowed $380.49 billion to buy houses, with sales volumes about half their peak in the early 2000s when there were almost 1.3 million fewer people in the country.

This was one of the issues Michael Cullen wanted to fix with his KiwiSaver scheme when he pointed out savings and investment are the foundation of future wealth of the nation and its people.

The unspoken rationale

As we’re regularly told, we’re not going to get rich as a nation buying and selling houses to each other, even if every policy setting tells you to do just that.

Enter finance minister Nicola Willis to the Financial Services Council’s annual conference, with the barbed statement that no serious political party will go into next year’s general election without a policy on superannuation and savings.

A cynic might quip that New Zealand lacks serious political parties, given their own propensity for self-preservation in rolling out slick campaigns of little substance, focused on trying not to scare the horses rather than putting together cohesive policies that recognise a government’s limitations in trying to fulfil a public’s thirst for everything everywhere all at once.

But that wouldn’t be nearly as satisfying as our political masters actually recognising that our long-running game of Jenga is running out of safe blocks to pull out from the bottom.

New Zealand’s social contract on savings and superannuation is going to have to incorporate where the money is coming from. That means both the public’s perception and the politicians’ pitching can’t be in isolation from how it will ripple through tax policy through to social welfare and health.

Because irrespective of what settings are palatable enough for our 120 elected members of Parliament to swallow, we’re the ones who are going to have to live with it – preferably within our means.

Image from Curious News.