PAUL MCBETH: A fair dinkum opportunity for the NZX

What does Cboe’s retreat from the West Island mean for New Zealand?

Paul McBeth is the editor of The Bottom Line and Curious News, and previously worked at BusinessDesk for 15 years. He’s owned shares of NZX since January 2024 and has been a member of the NZ Shareholders’ Association since February 2024.

There were a few muttered “strewths” across the Tasman this week when Cboe Global Markets – which some of us still call the Chicago Board Options Exchange – decided Australia wasn’t part of its core business and put its exchange up for sale.

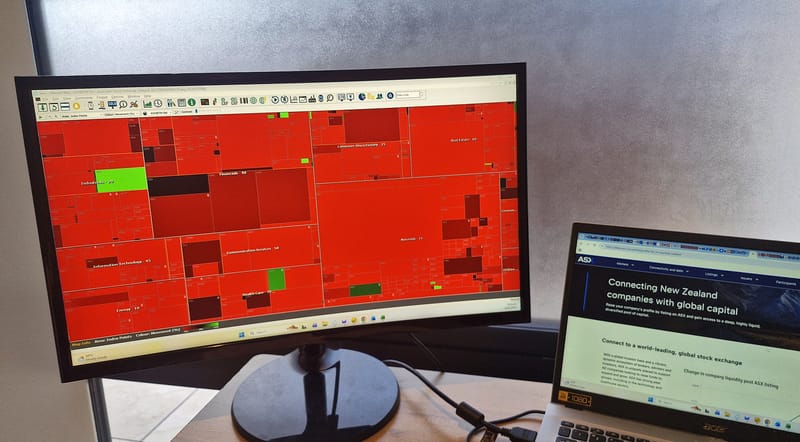

The reason it left some people gobsmacked was that the alternative to the dominant ASX – which accounts for a fifth of daily trading across the Tasman – had just been granted a licence to list new companies on its platform.

The Australian Securities & Exchange Commission – their equivalent of our Financial Markets Authority, but with slightly bigger teeth – has had a gutsful of the ASX, with a wide-ranging review underway into whether the stock exchange operator is up to the job after its aborted upgrade of the CHESS settlement system burned through hundreds of millions of dollars and added years to the much-needed refresh.

And in September, the Reserve Bank of Australia ticked off the ASX, saying it’s not meeting regulators’ expectations as an operator of critical national infrastructure.

Unsurprisingly, regulators wanted Cboe to put some competitive heat on the ASX to lift its game.

The thing is, much like any junior bourse can tell you, it’s hard yakka taking on an incumbent.

Make a noise and make it clear

It’s not just the weight of money behind an existing entity. There’s name recognition and understanding a certain level of service, plus the general inertia facing any upstart trying to convince potential customers that they’d be better served by a hungry new entrant.

In saying that, under Cboe’s ownership, the old Chi-X exchange has lifted its share of Australian trading volumes from just shy of 16% in 2022, its first full year of ownership, to almost 21% now.

That’s nothing to sniff at, albeit perhaps not quite that tasty for a multinational with US$4.09 billion of annual revenue and a net profit of US$764.9 million.

Cboe’s an entity big enough to tell its shareholders when buying the Chi-X assets in 2021 – which also included a Japanese exchange – that it wasn’t material to its business, letting them pore through their regulatory filings to see it added US$266.5 million of total assets, or roughly 10 times the US$26 million of annual revenue in calendar year 2020.

Which is where an overactive imagination can run wild, especially when someone far more sensible indulges you.

Because A$2 billion or so of daily turnover is a chunky amount of activity when you look longingly from this side of the Tasman, with some potentially helpful strategic positioning for a littler bourse like our NZX.

Two worlds collided

Without knowing the pricing structure and how much filters back to Cboe – which uses ASX’s clearing and settlement services – in New Zealand, the NZX generates $210,000 in trading and clearing fees for every $1 billion of traded value.

If the NZX’s split holds across the Tasman, where about 62% of that revenue comes from clearing fees, that’s still A$20.3 million of annual trading revenue for the Australian Cboe exchange – roughly a third of what the NZX generates from its core markets arm.

Sure, that’s top line revenue and Cboe has more than doubled its staff in Australia since buying the exchange, with 60 of the 86 people working for the Chicago giant in the Lucky Country focused on the Aussie market. But as NZ Shareholders’ Association chief Oliver Mander mused in The Long and the Short of It podcast, there’s bound to be areas of duplication to tighten up that cost line if the NZX were to go and kick the tyres.

Especially when you consider NZX’s New Zealand Clearing and Depositary Corp operates without a hitch these days and is backed by Tata Consultancy’s BaNCS software – which just happens to be the system the ASX opted for when it realised its blockchain pipedream wasn’t going to fly.

It might seem cheeky for the NZX to contemplate a move west, but the trans-Tasman exchanges are more buddy-buddy than we mere outsiders give them credit for, typically trying to work in lockstep on regional issues, such as the global move to one-day trading settlements.

Add it doesn’t take extravagant mental gymnastics to see how having an Australian bourse might help convince some of those reluctant brokerages to take another look at the wider NZX universe.

The last plane out of Sydney’s almost gone

Which isn’t to say the NZX needs to go west at any cost.

As Mander points out, you don’t want to see a board fritter away capital needlessly and the NZX has been pretty disciplined in managing shareholders’ money in recent years.

But it’s also going through the process of finding a new chief executive to replace the steadying hand of Mark Peterson when he waves goodbye in April, at a time when there’s real movement going on to improve the regulatory settings.

Keeping that momentum’s important in banging home the message that capital markets matter.

Sure, it might seem to be going at a glacial pace for those of us in the real world, but the wheels are turning and, fortunately for us, ASIC is more focused on the burgeoning issues in private credit funds than reviving public markets, with its latest roadmap picking up on some of the good ideas slowly working their way through Wellington.

It might simply be a self-interested flight of fancy, but there’s nothing quite as frustrating as seeing an opportunity missed.

Image from Umut YILMAN on Unsplash.